Idaho boasts a rich history that is intricately woven with the establishment of various historic forts.

These fortifications served as military, fur trading posts, and interaction points between the U.S. government and Native Americans.

Let’s explore these historic forts in Idaho and their significance.

Historic Forts in Idaho

| 1. Fort Boise | 6. Fort Henry |

| 2. Fort Hall | 7. Fort Lemhi |

| 3. Fort Lemhi | |

| 4. Fort Sherman (Fort Coeur d’Alene) | |

| 5. Fort Lapwai |

1. Fort Boise: A Nexus of Trade, War, and Expansion

The Hudson’s Bay Company constructed Fort Boise in 1834, a pivotal year of increased movement and activity in the Pacific Northwest due to fur trading. Under the leadership of Thomas McKay, a seasoned fur trader, the fort was erected near the mouth of the Boise River, close to its confluence with the Snake River.

Its strategic location made it a bustling hub for fur traders, especially those making their way along the treacherous path of the Oregon Trail.

This original Fort Boise, commonly called Old Fort Boise, primarily catered to the booming fur trade. The fort served as a countermeasure against the American-held Fort Hall, 483 km (300 miles) to the east.

With the decline in the fur trade and increasing hostilities with the local Native American tribes, particularly after several deadly skirmishes, the significance of the fort dwindled.

By the early 1850s, after years of flooding and Indian attacks, the Hudson’s Bay Company abandoned the fort.

Rise of the New Fort Boise

The 1860s saw a surge in gold seekers flocking to the Boise Basin, driven by the promise of gold following significant regional discoveries.

The influx of settlers and the potential for conflict with the Native American populations underscored the need for a military presence.

Recognizing this, the U.S. government commissioned Major Pinkney Lugenbeel 1863 to establish a new fort. This new establishment, often called Boise Barracks or the new Fort Boise, was strategically placed about 64 km (40 miles) from the original site.

The 1860s were tumultuous times in American history. While the Civil War raged in the East, the new Fort Boise was embroiled in the Snake War (1864-1868), a series of conflicts between Native American tribes and white settlers in the Pacific Northwest.

The fort served as a critical base for U.S. Army operations, providing shelter, supplies, and a strategic advantage.

Legacy and Preservation

By the early 20th century, much of the fort’s military relevance had decreased.

However, its historical significance was not forgotten. In the 1920s, parts of the fort were transferred to the Veterans Administration (now the Department of Veterans Affairs) and were utilized for various purposes, including medical care.

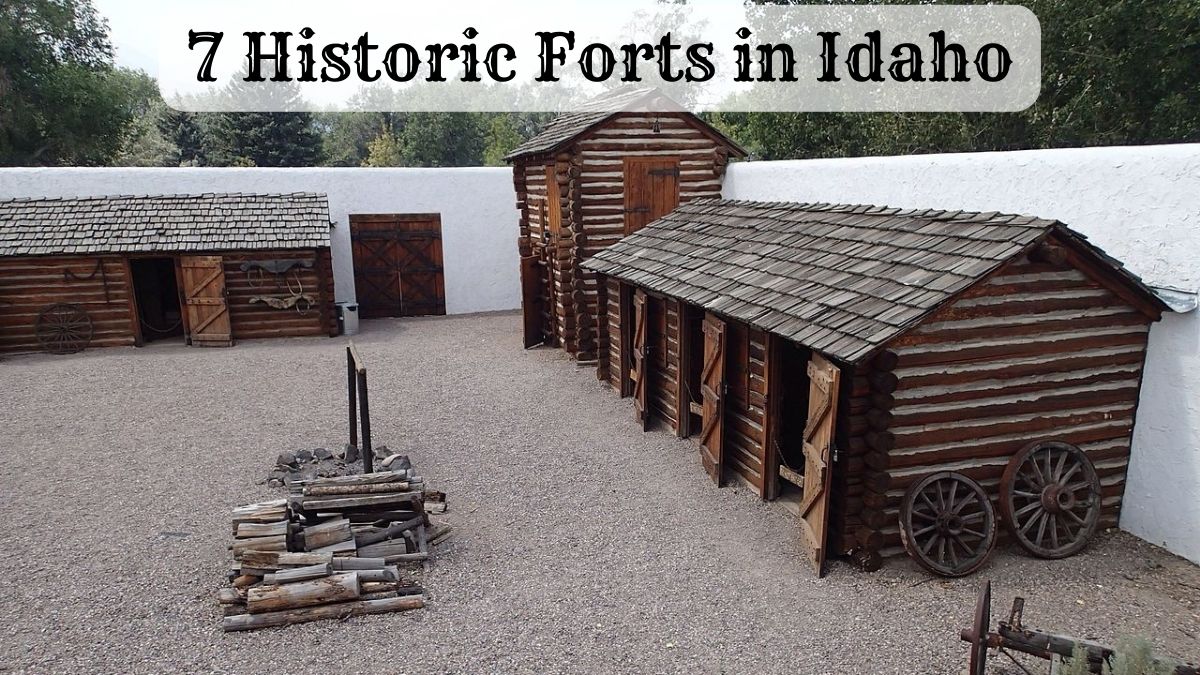

Today, the fort’s legacy is preserved by the National Park Service. The grounds of the original Fort Boise can be visited, and a replica built in the 1970s in Parma, Idaho, offers visitors a tangible connection to the past.

This replica, funded by the Idaho Elks Rehabilitation Hospital and crafted with the assistance of local historians, provides an immersive experience, transporting visitors back to the days when fur traders, gold seekers, and soldiers walked the grounds of Fort Boise.

2. Fort Hall: Crossroads of the West

Fort Hall was established in the summer of 1834 by an ambitious Boston entrepreneur, Nathaniel J. Wyeth, who saw potential in the Western fur trade.

Unlike many forts rooted in military aspirations, Fort Hall was conceived as a commercial venture — a fur trading post in the heart of the Snake River Valley in southeastern Idaho, near the present-day town of Pocatello.

Its construction coincided with the burgeoning westward expansion of the United States, making it an immediate asset for the country’s manifest destiny.

The fort quickly became an indispensable stopover for emigrants traveling the Oregon Trail, offering respite and replenishment. By the late 1830s, it had become one of the vital supply points along the trail, serving thousands of settlers, fur traders, and even missionaries heading to the Oregon country.

Transfer of Ownership and Expansion

Fort Hall’s significance increased when it was purchased by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1837. Under their ownership, the fort became an even more prominent hub for trade and migration.

Its location was pivotal — it stood near the junction of the Oregon Trail with paths leading to the California Trail and the later Mormon Trail, thus influencing the passage of countless pioneers heading to various destinations in the West.

As a fur trading post, it welcomed traders from all over the region, including the Flathead, Bannock, and Shoshone tribes, among others. The exchange of beaver pelts, buffalo robes, and horses became commonplace within its walls.

Decline and Legacy

With the decline of the fur trade in the 1840s and the increasing flood of emigrants towards the California gold fields, the fort’s commercial utility began to fade.

The Hudson’s Bay Company, recognizing the changing times, abandoned Fort Hall in 1856.

However, the legacy of Fort Hall would be firmly cemented into the annals of American history. The surrounding area grew, and the town of Fort Hall developed.

Today, the original site of the fort is located on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation, home to the Shoshone-Bannock tribes.

Fort Hall Today

Recognizing the historical significance of Fort Hall, the Bannock County Historical Museum, in collaboration with the community, established a replica of the fort.

This replica is a vivid historical exhibit, providing a window into the lives of those who passed through its gates — the trappers, traders, Native Americans, and emigrants who shaped the region’s history.

Visitors to the replica can see structures reminiscent of the original fort’s buildings, including the trade store, blacksmith shop, and living quarters.

It’s not just a monument to the past but an educational resource that tells the story of the Oregon Trail, the fur trade, and the interaction between Native Americans and emigrants during a pivotal era of American expansion.

3. Fort Lemhi: A Brief Union of Faith and Frontiers

Fort Lemhi was established as a mission in the spring of 1855 by a group of Mormon pioneers under the direction of Brigham Young, the leader of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church).

Unlike many forts of the era that served military or trading purposes, Fort Lemhi’s creation was rooted in the LDS Church’s desire to expand and teach agriculture to the Native Americans.

The fort was named after King Lemhi from the Book of Mormon, marking the northernmost settlement of the Mormons at that time.

Interaction with Native Americans

The site chosen for Fort Lemhi was in the territory of the Shoshone and Bannock tribes. Initially, the relationship between the Mormon settlers and the Native Americans was cooperation and mutual benefit.

The missionaries aimed to convert the Shoshone-Bannock people to Christianity while helping them learn farming techniques to improve their sustenance practices.

The fort was located along the Salmon River in present-day Idaho and was set up as an autonomous agrarian commune. The fort’s design included a wooden barrier for protection, with cabins, a church, and a school within its perimeter.

Rising Tensions and Abandonment

The harmonious start to the relations between the Mormons and the Native Americans, however, did not last.

The Shoshone and Bannock tribes faced increasing pressure and disruption of their lands due to the continuous influx of settlers. Additionally, cultural differences and misunderstandings contributed to growing tensions.

Despite efforts at peaceful coexistence, the situation deteriorated. In February 1858, a confrontation led to the death of two Mormon settlers.

The resulting fear and tension compelled the remaining settlers to abandon Fort Lemhi and return to the more established Mormon settlements in Utah.

The Aftermath and Memory

After the abandonment by the Mormon settlers, Fort Lemhi faded from prominence. The structures fell into disrepair, and the area reverted to its natural state, with little to mark the short-lived experiment in Mormon and Native American relations.

Today, Fort Lemhi is remembered more for its intent than its longevity or impact. No substantial physical remnants of the fort remain, but the story of Fort Lemhi is preserved in the annals of LDS Church history and the shared heritage of the Shoshone and Bannock peoples.

It is a reminder of the complex interactions between settlers and Native Americans during America’s westward expansion.

4. Fort Sherman: Guardian of the Coeur d’Alene

Fort Sherman, initially christened Fort Coeur d’Alene, was established by the U.S. Army in the 1870s in the scenic region of Coeur d’Alene, Idaho.

The post was constructed to assert a U.S. military presence in the Pacific Northwest, mainly to oversee the interactions between settlers and the Native American tribes and to maintain peace in the area.

The fort was named after General William T. Sherman, a prominent figure in American military history, mainly known for his role in the Civil War.

Sherman visited the area in 1883 and recognized the fort’s strategic position, not only for its military advantage but also for its potential to support westward expansion and settlement.

A Center of Military Activity

Fort Sherman became a bustling military post where troops were staged for various campaigns, including suppressing the Bannock uprising and the Coeur d’Alene labor strikes.

Its establishment also helped pave the way for the town of Coeur d’Alene, which grew alongside the military post.

The fort’s infrastructure included barracks, a hospital, stables, and a schoolhouse, which also served as a chapel.

These buildings were erected not only to meet the immediate needs of the stationed troops but also to support their families and the community rapidly developing around the military post.

Transition to Community Use

As the threats that prompted the establishment of Fort Sherman diminished and the frontier closed, the fort’s military importance waned.

In the early 20th century, the fort was decommissioned, and the federal government repurposed the land and buildings. Some parts of the land were allocated to the state of Idaho, and other sections were used for educational purposes.

Today, several of the original buildings have been repurposed and serve as community centers and educational facilities.

The community center, which stands on the grounds of the former fort, is a particularly vibrant part of local life in Coeur d’Alene, hosting various events and activities that cater to the public.

Preserving the Legacy

The historical significance of Fort Sherman has been acknowledged with its inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places.

This designation helps preserve the surviving structures and the memory of the fort’s role in the regional and national history of the United States.

One of the most visible remnants of the fort’s past is the chapel, which is one of the oldest buildings in the region and serves as a historical landmark.

It offers a glimpse into the life of soldiers and settlers during a transformative period in Idaho’s history.

5. Fort Lapwai: A Symbol of Encounter and Conflict

Fort Lapwai emerged from transforming a missionary presence into a military one in the heart of the Nez Perce territory in North Central Idaho.

It was initially a mission site called Lapwai Mission, established by Henry and Eliza Spalding in 1836 to work with the Nez Perce tribe.

By the 1860s, following the discovery of gold in Nez Perce land and the subsequent influx of white settlers, the mission site’s purpose shifted.

In 1863, the U.S. Army constructed Fort Lapwai to facilitate the maintenance of the new reservation system and manage the relations with the Nez Perce tribe, amid growing pressures and encroachments on their land.

The Nez Perce War and Chief Joseph

Fort Lapwai gained historical prominence as a strategic military post during the Nez Perce War of 1877.

The conflict arose due to the federal government’s attempts to force the Nez Perce onto a much smaller reservation, which led to a series of engagements and battles.

The fort served as the operational center for the U.S. Army’s pursuit of the Nez Perce under the leadership of Chief Joseph.

Chief Joseph, known for his leadership and advocacy for his people, became renowned for his principled resistance to the removal of his band from their ancestral homeland.

The fort played a significant role in the U.S. Army’s attempts to subdue the Nez Perce and was the site of significant, and often tragic interactions between the army and the tribe.

Post-War and Legacy

After the Nez Perce War, Fort Lapwai operated as a military post until the late 1880s. Its presence was a constant reminder of the U.S. government’s authority in the region and the changing dynamics between the Native Americans and the encroaching settlers.

The military abandoned Fort Lapwai in 1884, and the site was repurposed for various uses, including an asylum for the insane, and later, as the headquarters for the Nez Perce National Historical Park.

The park, established in 1965, encompasses a collection of sites significant to the Nez Perce people and the region’s history.

Today, some buildings of the original Fort Lapwai still stand, serving as a sobering reminder of the complex and often turbulent interactions between the U.S. Army and the Nez Perce tribe.

The site is also a place of education and remembrance, providing insight into the Nez Perce’s resistance and resilience and the fort’s role in one of the defining conflicts of the American West.

The Fort Today

The legacy of Fort Lapwai and its historical importance is not forgotten. It is commemorated through interpretive sites, trails, and displays that tell the story of the Nez Perce people and their struggles.

For many, it is a place to reflect on the past and to acknowledge the enduring spirit of the Nez Perce tribe, as well as the complexities of American history.

6. Fort Henry: The Echoes of a Fleeting Frontier Post

Fort Henry was established in 1810 by the enterprising men of the Missouri Fur Company, a venture spearheaded by Manuel Lisa and other notable frontiersmen of the era.

This company, formed in St. Louis, Missouri, was one of the early American fur trading enterprises venturing into the untamed wilderness of the Rocky Mountains.

Nestled in the wild, near what is now St. Anthony, Idaho, Fort Henry was strategically placed to tap into the lucrative beaver fur trade.

The region was rich in wildlife and offered a gateway to the untamed lands that beckoned trappers and traders alike. It served as a base for trapping expeditions, a hub for commerce, and a haven in the remote expanse of the early 19th-century American West.

The Challenges and Demise

The life and existence of Fort Henry were fraught with challenges. The men who manned this isolated outpost faced the dangers of harsh winters, the uncertainty of supply routes, and the complexities of interactions with Native American tribes, whose ancestral lands they were infringing upon.

Moreover, competition with other fur trading companies, such as the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company, both of which had strong footholds in the western fur trade, was intense.

These pressures, combined with the logistical difficulties inherent in maintaining such a remote outpost, led to Fort Henry’s short operational life.

By the close of the fur trade season 1811, the fort had served its purpose, and the Missouri Fur Company decided to abandon the site.

The exact reasons remain a blend of historical speculation and deduction, with factors likely including the scarcity of furs due to over-trapping, Native American resistance to foreign incursion, and the sheer isolation of the location.

Historical Footprint and Commemoration

Despite its brief existence, Fort Henry holds the distinction of being among the earliest American fur trading forts in the Pacific Northwest.

While it did not have the enduring presence of other forts, it was a precursor to the more permanent settlements and trading posts that would dot the landscape as the fur trade expanded.

Today, there is little left of the original Fort Henry. The site near St. Anthony is a quiet testament to the transient nature of frontier outposts.

It is remembered primarily through historical markers and the research of historians who piece together the story of the fort and its role in the broader narrative of the American fur trade and the exploration of the West.

7. Fort Lemhi: A Short-Lived Mormon Outpost

Fort Lemhi was established in 1855 by a group of Mormon missionaries with the intent to convert the Native American populations, specifically the Shoshone people, to Christianity.

The fort was named after King Lemhi from the Book of Mormon, reflecting the religious impetus behind its establishment.

The missionaries who set up Fort Lemhi were sent by Brigham Young, the second President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who was also the founder of Salt Lake City and a leading figure in the westward expansion of Mormon settlers.

The fort was part of a broader mission to establish a Mormon corridor through the American West, stretching from the Great Basin of Utah to California.

Life and Strife at Fort Lemhi

The missionaries not only aimed to proselytize but also hoped to foster positive relations and trade with the Shoshone.

The settlers began to farm the land, and for a brief period, there was a mutually beneficial relationship between the Mormons and the Native Americans.

Fort Lemhi served as a community center where agricultural practices were shared, and cultural exchanges took place.

However, as often in such frontier interactions, tensions eventually arose. Misunderstandings, cultural differences, and competition for resources led to conflict.

The Shoshone, growing wary of the intentions and the encroaching settlement practices of the Mormons, became less welcoming.

These escalating tensions culminated in a violent incident in 1858, in which a group of Shoshone attacked Fort Lemhi, killing two missionaries and driving the settlers out.

The fort was subsequently abandoned, and the Mormons retreated to the more established areas in Utah.

The Legacy of Fort Lemhi

The story of Fort Lemhi is one of aspiration and adversity. The missionaries’ ambition to extend their religious community into the heartland of Native American territories faced the harsh realities of frontier life and the imperative of Native Americans to defend their homelands.

Today, the site of Fort Lemhi is a historical footnote, often overshadowed by more significant conflicts and settlements of the time.

Yet it remains a point of interest for those studying the Mormon expansion, the interactions between settlers and Native American tribes in the mid-19th century, and the broader tapestry of Idaho’s history.

Related: 10 Historic Forts in Nevada

Conclusion – Historic Forts in Idaho

Idaho’s historic forts are a testament to a time when fur traders, Native Americans, and the U.S. government collided in their ambitions. These sites, some now on the National Register of Historic Places, serve as a window into the past – a world where the Oregon Trail saw a mix of military expeditions, trade, and exploration.

Local historians, with the aid of oral histories and federal documents like the Dictionary of the United States Army, continue to preserve this rich tapestry of history for future generations.

Whether it’s the interpretive center at the Fort Hall replica or the preserved building quarters of Fort Sherman, Idaho’s historic forts remain a popular destination for history enthusiasts.

Thanks for reading, and if you have visited any of these forts, we would love to hear about your experience in the comments section below.

Cory is a website owner and content creator who enjoys fishing, history, coin collecting, and sports, among other hobbies. He is a husband and father of four.

Romans 15:4 For whatever was written in former days was written for our instruction, that through endurance and through the encouragement of the Scriptures we might have hope.

What can you tell us about Camp Connor, by Soda Springs, Idaho?

Fort Lemhi, the Mormon outpost was named Fort Limhi (Lemhi are the Indians, Limhi is the Book of Mormon character).

Thanks for clarifying that James!