Missouri, nestled at the confluence of the Missouri River and Mississippi River, boasts a rich history dotted with military installations, trading posts, and historic forts that played an essential role in American history.

From the early settlers arriving in St. Louis to the Clark Expedition mapping the American frontier, the state’s fortifications have always been an intrinsic part of its story.

In this article, historic forts in Missouri, we will explore ten forts that shaped the history of this fascinating and historically significant state.

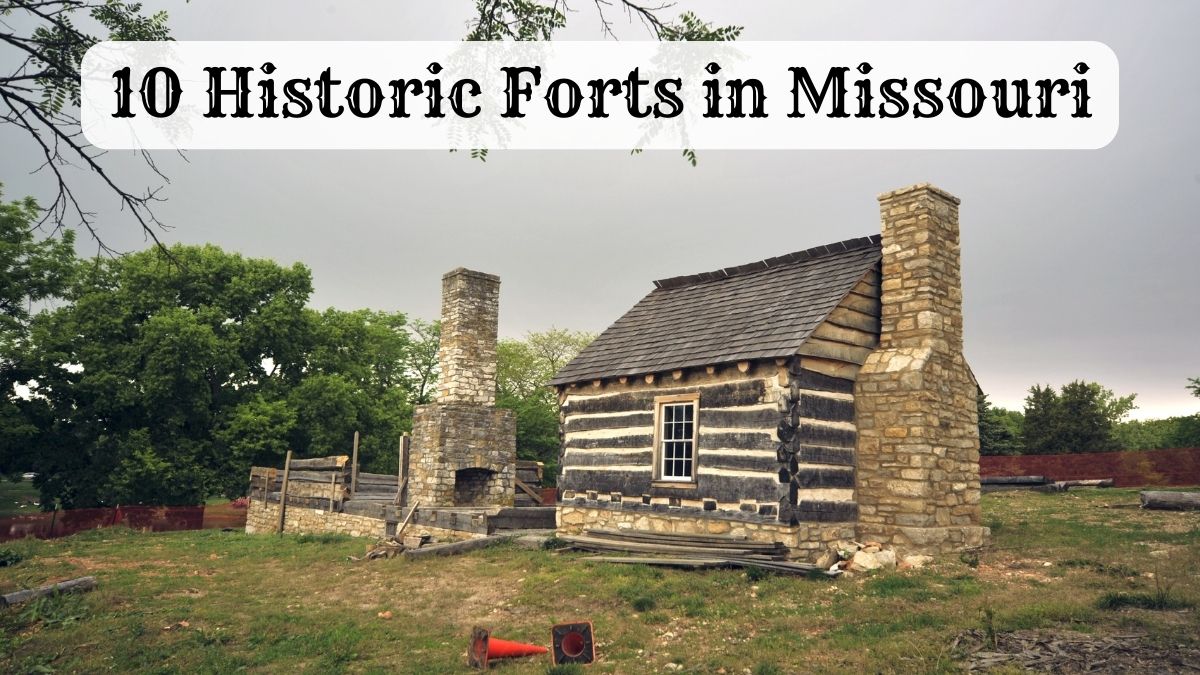

10 Historic Forts in Missouri

| 1. Fort Osage | 6. Fort Charette |

| 2. Fort Belle Fontaine | 7. Fort Zumwalt |

| 3. Fort D | 8. Fort Carondelet |

| 4. Jefferson Barracks | 9. Fort Davidson |

| 5. Fort Orleans | 10. Fort Cap-Au-Gris |

1. Fort Osage: The Early Settlers’ Trading Post

Resting on the western fringes of Missouri’s landscape, Fort Osage, also known as Fort Clark or Fort Sibley, played a crucial role in the early 19th-century American frontier. Today, the historical site resides in what we know as Sibley, Missouri.

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the iconic American explorers, highlighted this location during their epic journey up the Missouri River in 1804. Noting its high elevation, offering a commanding view, and its proximity to the river, they marked it as a spot of significance.

In that very year, Pierre Chouteau, a pivotal figure in the fur trading world and an envoy for the Osage, took Osage chiefs to the nation’s capital. President Thomas Jefferson met them, offering promises of a trading post.

Jefferson, keen on expanding Federal trading posts, viewed them as a way to outmaneuver private traders and cultivate strong relations with the Native American communities.

Laying the Fort’s Foundation

By September 1808, William Clark constructed Fort Osage on the site they had earmarked years earlier. Subsequently, in November, Pierre Chouteau formalized the Treaty of Fort Clark with select Osage Nation members.

This agreement allowed the establishment of Fort Osage, ensuring the Osage’s protection against other tribal adversaries. In exchange, the Osage ceded their eastern territories to the U.S., confining them to a narrow strip on Missouri’s western edge.

Operational Epoch

Under the leadership of Captain Eli Clemson, Fort Osage officially began its operations in 1808. It also bore the informal name “Fort Clark” in a nod to William Clark. The fort quickly evolved into a prominent stopover for travelers on the Missouri, with even the likes of the legendary Daniel Boone gracing its environs in 1816.

During the War of 1812, despite being distant from the primary theaters of war, the fort was abandoned in 1813. It resumed operations in 1815 post-war, thriving as a trading center, selling goods at competitive rates, benefiting from its strategic position.

Decline and Closure

However, the Adams-Onís Treaty and the War of 1812’s conclusion significantly reduced external threats. As the Osage surrendered more territories, the U.S. shifted its trading focus to Fort Scott in Kansas.

Fort Osage eventually shuttered its operations in 1822. Over the subsequent years, its once-prominent structures were dismantled and repurposed by local settlers.

Fort Osage’s Revival

The 1940s witnessed archaeologists unearthing Fort Osage’s buried foundations. Leveraging the detailed surveys orchestrated by William Clark, a meticulous reconstruction was undertaken between 1948 and 1961.

Today, This reincarnation is the Fort Osage National Historic Landmark, a proud entry in the National Register of Historic Places.

Visiting Today’s Fort Osage

Under the stewardship of Jackson County Parks and Recreation, Fort Osage beckons history aficionados. The Fort Osage Education Center inaugurated in 2007, offers a deep dive into the region’s geological, cultural, and historical tapestry.

Visitors can engage with exhibits and immerse themselves in living history demonstrations, bringing the early 19th-century military and civilian life to life.

2. Fort Belle Fontaine: Gateway to the American West

Situated in St. Louis County, Missouri, and overlooking the meandering courses of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers across from Alton, Illinois, Fort Belle Fontaine (earlier known as Cantonment Belle Fontaine) has been a cornerstone in the expansionary history of the United States.

Recognized as the premier U.S. military installation west of the Mississippi River, this fort has witnessed several pivotal expeditions that mapped the contours of the American West.

Historical Legacy

- The Strategic Setting: Nestled on the Missouri River’s south bank, the fort’s history stretches back to its days as a Spanish military post. But its fate changed with the unfolding of the Louisiana Purchase.

With a treaty inked between the U.S. Government and representatives of the Sac and Fox tribes, spearheaded by William H. Harrison, the fort metamorphosed into a U.S. fur trading post by 1805. Rudolf Tiller took the reins as the factor, with Colonel Thomas Hunt leading the military operations. - Shift in Purpose: By 1808, its role as a trading post had waned. For the next 17 years, until 1826, it served a purely military role. Between 1809 and 1815, during the turbulence of the War of 1812, the fort emerged as the nerve center of the Department of Louisiana.

It was in good company with its sister forts – Fort Osage and Fort Madison – that controlled the trade dynamics with the native tribes. - Resting Grounds of the Brave: The establishment of the Old Fort Belle Fontaine Cemetery in 1809 by Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Bissell marked another crucial chapter. This cemetery, located a short walk from the fort’s buildings, became the final resting place for many military personnel.

The eroding tombstones, a testament to the passage of time, still stand as reminders of those who served at the fort.

Preservation and Legacy

Despite the ravages of time and the decay of memories, efforts to preserve the fort’s legacy have been relentless.

The Fort Belle Fontaine County Park, under the guardianship of St. Louis County’s park system, keeps the memories of this historic fort alive. Additionally, its archaeological significance earned it a spot on the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

3. Fort D and the Cape Girardeau Legacy

With its storied past, Missouri has been a focal point in American history, particularly during the Civil War era. One of its most iconic sites is Fort D, Cape Girardeau. Overlooking the mighty Mississippi River, this fort is a testament to the era’s military strategies and brave soldiers.

Construction of Fort D

Fort D’s construction journey began on August 6, 1861. Lieutenant John W. Powell of Illinois led this endeavor. Powell wasn’t just a military strategist; he had a connection to Cape Girardeau, recruiting men from the town to fight for the Union army. These brave souls were named Battery F, 2nd Illinois Light Artillery, given his Illinois roots.

However, Powell’s tryst with history didn’t end at Fort D. During the Battle of Shiloh on April 6, 1862, Powell’s command was dramatically cut short when a bullet pierced his wrist.

The severe injury led to the amputation of his arm. Undeterred by this setback, Powell later achieved fame by successfully navigating the Colorado River through “the Grand Canyon” in 1869 – a name he bestowed upon this natural wonder.

Today, Fort D stands with its original earthwork walls, constructed in 1861 and restored in 1936. These walls tell tales of strategies with sally ports and rifle pits.

The fort was a formidable stronghold armed with mighty 32-pounder and 24-pounder cannons. The 32-pounder cannons, with their ability to shoot a massive solid round over a mile and their sheer weight, are particularly noteworthy.

Despite its imposing structure, Fort D never witnessed direct combat. While the Battle of Cape Girardeau raged on April 26, 1863, it occurred west of the city, sparing the fort from battle scars.

Other Fortifications in Cape Girardeau

Fort D is not the lone sentinel of Cape Girardeau’s Civil War heritage. The area once boasted other fortifications, though Fort D is the only one that survives today.

Fort A’s unique grist-grinding windmill stood north of the city’s downtown. Fort B found its place where the present-day Academic Hall of Southeast Missouri State University stands.

Fort C was erected at the end of Bloomfield Road. The region also featured smaller defensive structures, including Battery A and B, and rifle pits that marked Perry Avenue and the current location of the Southeast Missouri Hospital.

Preserving Fort D for Modern Generations

Fort D’s significance hasn’t faded over time. Recognizing its historical value, efforts in the early 20th century protected it from urban development.

The 1930s saw the Works Progress Administration (WPA) step in, repairing the earthworks and constructing a stone blockhouse in 1936. This blockhouse has since served various purposes, underlining Fort D’s adaptability and resilience.

In recognition of its storied past and architectural significance, Fort D was proudly listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2019.

4. Jefferson Barracks Military Post

The Jefferson Barracks Military Post is an iconic location along the Mississippi River in Lemay, Missouri, just south of St. Louis. With an extensive history stretching from 1826 to 1946, it has been a significant establishment in the U.S. military narrative, notably as the longest-operating U.S. military installation west of the Mississippi.

Today, it serves multiple roles, including housing the Army and Air National Guard and a base for Veterans Affairs.

Key Historical Points

- Establishment (1826): The foundation was driven by General Edmund P. Gaines, Brig. General Henry Atkinson, explorer William Clark, and Missouri Governor John Miller. It was named in honor of Thomas Jefferson.

- Black Hawk War (1832): Troops from Jefferson Barracks were essential in managing the conflict, which resulted in the capture of Chief Black Hawk.

- Mexican–American War (1846–1848): The post played a pivotal role, serving as a pivotal rest and supply station for U.S. troops heading to Mexico.

- Civil War (1861–1865): The barracks became a significant medical facility, treating over 18,000 soldiers during the war. It was also a recruitment center for the Union.

- Spanish–American War (1898): Reinforcing its reputation, the barracks served as a recruitment and organization center during the conflict.

- World War I: Notable for the pioneering parachute experiments in 1912 and as a training hub during the war.

- World War II: The barracks furthered its reputation by being a prominent reception center for draftees and an Army training site.

- Decommission (1946): Post-World War II, the site was decommissioned, and portions sold off. It saw various uses, including housing, schools, and church functions.

Present Day Usage

Today, Jefferson Barracks enjoys a multifaceted role. It is a military activity hub, with the Army and Air National Guard’s presence. The vast space has been used with parts converted to county parks, and it is also home to the Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery.

The area has also seen educational, recreational, and housing developments, making it a key historical and functional landmark in Missouri.

5. Fort Orleans: France’s Foothold in Colonial America

Perched near the confluence of the Grand River and the Missouri River, Fort Orleans, often called Fort D’Orleans, is the first European structure along the Missouri River.

Located near modern-day Brunswick, the fort symbolizes early European ambitions in North America, and its remnants whisper tales from the era when France hoped to dominate a vast stretch from Montreal to New Mexico.

Foundation and Intent

Established in 1723 by Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont, the fort was envisioned as the command post overseeing the sprawling Louisiana territory, newly claimed by France. Bearing a name reminiscent of New Orleans, it was a nod to the Duke of Orléans.

De Bourgmont’s Intriguing Past

Having previously led at Fort Detroit, de Bourgmont became notorious after deserting his post following a controversial skirmish with the Ottawa tribe in 1706.

He subsequently chose to live among Native Americans, navigating the lower Missouri, engaging in unauthorized fur trades, and even settling with a Missouri wife, producing children of mixed descent.

Despite his unconventional path, de Bourgmont penned influential works like “Exact Description of Louisiana” and “The Route to Be Taken to Ascend the Missouri River,” which greatly informed early maps of the region.

From Outlaw to Hero

By 1718, French authorities shifted their perception of de Bourgmont, seeing him as an asset rather than a renegade.

His extensive knowledge of the territory and his close relationships with native tribes became invaluable, especially as news broke of the Pawnee’s destruction of the Villasur expedition, halting Spanish advances into the Missouri River Valley.

Fort Establishment and De Bourgmont’s Ventures

Despite initial resistance and debates regarding the necessity of a fort, Bourgmont eventually heeded his orders and established Fort Orleans in 1723.

His exploratory efforts continued, with a significant journey in 1724 to the Kaw village and subsequently the Great Plains, fostering peace and trade relations with numerous tribes.

The Fort’s Demise

By 1726, Fort Orleans’ star had dimmed. Stories vary; some suggest a devastating Native American attack while others believe it was abandoned. Despite its end, Fort Orleans’ brief but vibrant existence became an emblem of European endeavors in colonial North America.

Location Uncertainties

The fort’s exact location remains elusive, with Lewis and Clark seeking its remnants in 1804 but finding no clear traces. Present-day speculations suggest potential sites near Malta Bend, the north bank of the Missouri River by Wakunda Creek, or even an island along the river.

Structures in Brunswick, Missouri, are believed to be remnants connected to the fort’s history.

6. Fort Charette

Fort Charette, positioned near modern-day Washington, Missouri, was a landmark established in 1790 by French fur trader Joseph Chadron. Nestled on the Missouri River’s banks, this trading post was a beacon for explorers and pioneers in its prime.

When the Corps of Discovery, helmed by Lewis and Clark, embarked on their journey along the Missouri River, they took special note of Fort Charette. In their detailed logs, they highlighted it as the last white settlement they encountered.

Surrounding this fort, the village of La Charette sprang up, becoming one of the West’s early melting-pot communities. It was a unique blend of diverse backgrounds, from Native Americans and African Americans to immigrants from France, Spain, and Germany.

The strategic placement of Fort Charette made it a frequent stop for many iconic figures who played pivotal roles in America’s early frontier history. Individuals such as Daniel Boone, Zebulon Montgomery Pike, and John Colter were known to pass through its gates.

Floods Decimate The Fort

However, nature’s wrath spared no historical monument. In the floods of 1842-43, the powerful currents of the Missouri River erased both the fort and the La Charette village from the landscape.

Yet, the spirit of Fort Charette was indomitable. Its remnants were discovered in a nearby farm field, leading to its meticulous relocation and rebuilding in Washington.

Fort Charette Today

Today, the rejuvenated Fort Charette offers a panoramic view of life on the frontier. The trading post intricately portrays the barter system, the blacksmith’s shop emphasizes the era’s essential crafts, and the living quarters, adorned with period artifacts and furnishings, transport visitors back in time.

The restored Fort Charette remains a living testament to the vibrant history and cultural mosaic that laid the foundation for the United States.

7. Fort Zumwalt

Fort Zumwalt Park, located in O’Fallon, Missouri, covers an expansive 48 acres and is characterized by the rejuvenated homestead fort of Jacob Zumwalt. The park offers a serene 4-acre Lake Whetsel with amenities such as a picnic pavilion, shelter house, and a dedicated playground for children.

The park is a hub for festivities, hosting the annual “Celebration of Lights” and is also home to the St. Charles Model Railroad Club and the historic Darius Heald Home.

Jacob Zumwalt: The Founder

A veteran of the Revolutionary War, Jacob Zumwalt chose a hill for his residence, which was part of a vast Spanish land grant acquired in 1796. The land stretched across both sides of Belleau Creek. Completed in 1798 and expanded over the years, Zumwalt’s hewn-log house stood out with its unique Pennsylvania German construction details.

This home was the venue for the first Methodist sacrament in Missouri in 1807. When the War of 1812 brought unrest, the home was a refuge for local families, earning the title “Zumwalt’s Fort”. The threats from Native Americans ceased in 1815, bringing peace to the region.

After Zumwalt’s departure, the Heald family became the subsequent major owners, purchasing the property in 1817. The fort remained with them for almost a century before undergoing multiple ownership changes.

The historical importance of the fort was recognized with the installation of a marker in 1929. The 1930s witnessed the site’s transformation into a state park, following its acquisition by the state.

Restoration and Modern-Day Relevance

As the decades passed, the fort evolved from a local sanctuary to a sought-after spot for travelers. After the archaeological excavations in the 1970s, ownership transitioned to the City of O’Fallon in 1978.

Subsequently, the O’Fallon Community Foundation embarked on the fort’s restoration, culminating in its complete reconstruction by 2015.

Fort Zumwalt’s influence extends to the educational realm, with the Fort Zumwalt School District R-II and several high schools bearing its name. Furthermore, the Darius Heald Home, built in 1884 near the fort, represents the region’s architectural evolution, having been meticulously restored over the years.

8. Fort Carondelet

Fort Carondelet was built in 1795 as an early fur trading post in Spanish Louisiana, located along the Osage River in Vernon County, Missouri. Managed initially by the Chouteau family, it also fostered good relations between the Spanish colonial government and the Osage Nation.

However, by 1802, the fort changed hands and was subsequently abandoned.

Origins and Construction

Osage Nation and Early Traders Beginning in the mid-1700s, the Osage Nation engaged in fur trade with French and Spanish settlers. Prominent among the traders were the French brothers Pierre and Auguste Chouteau, based out of St. Louis. By 1787, the brothers had established a temporary trading post along the Osage River.

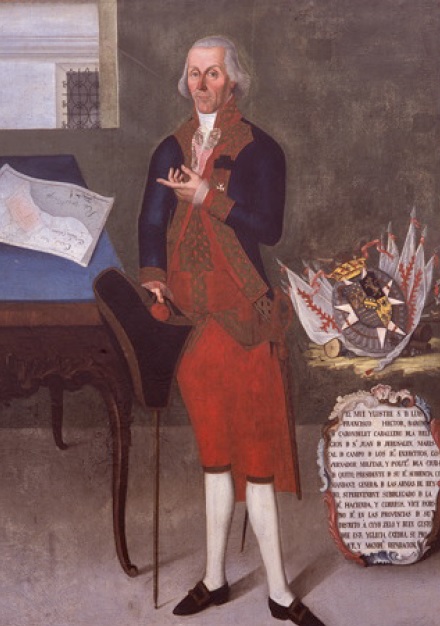

The inception of Fort Carondelet The idea for a fort in western Missouri was initially proposed in 1791 by Spanish Governor-General Esteban Rodríguez Miró. Before construction could commence, Miró was replaced by Francisco Luis Héctor de Carondelet.

Concerned about alliances between the Osage and the French, Carondelet held a peace meeting with Osage chiefs in 1794, leading to an agreement to allow the fort’s construction. Auguste Chouteau financially supported the project, providing a detailed blueprint for the fortification.

Use and Abandonment

Chouteau’s Operations Once completed in 1795, Fort Carondelet functioned as the westernmost outpost for the Chouteau trading operations rather than a military stronghold. The Chouteaus immersed themselves in the local culture, gaining acceptance from the Osage Nation, though causing envy among other tribes.

Expansion and Decline Under Pierre Chouteau’s leadership, trade expanded to other Osage settlements near the Arkansas River by 1796. However, by 1800, rival traders demanded an end to the Chouteau’s trading monopoly. The fort was subsequently sold in 1802 to Manuel Lisa, who opted to abandon it. By the time Zebulon Pike visited in 1806, the fort was already in ruins.

Remnants and Recent History

Archaeological Evidence In 1874, a travel guidebook highlighted the remains atop Halley’s Bluff, believed to be vestiges of the old fort. The site was described as having distinct structures suggestive of a former outpost.

Church Occupancy During the early 20th century, a Mormon offshoot group, known as the Church of Christ at Halley’s Bluff, controlled the property. Post-1970s, the compound became the Church of Israel property, associated with the Christian Identity movement.

Infamously, it was home in the 1980s to Eric Robert Rudolph, responsible for the 1996 Centennial Olympic Park bombing.

9. Fort Davidson

Fort Davidson was situated near the town of Pilot Knob, Missouri. During the American Civil War, it became the focal point of the Battle of Fort Davidson. Constructed by Union Army soldiers, the fort successfully fended off Confederate advances on September 27, 1864, during Price’s Raid.

However, the Union garrison later decided to detonate the fort’s magazine and abandon the area. This historic battleground now has a mass grave for the fallen. After the war, various entities owned the land, including a mining company, private owners, and the US Forest Service.

In 1968, it was designated as the Battle of Pilot Knob State Historic Site under the Missouri State Park system, and two years later, the fort was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

By 2020, the park featured a visitor center housing a museum, which showcased items like Brigadier General Thomas Ewing Jr.’s sword. Remnants of the fort’s walls and the explosion crater remain visible today, alongside a monument signifying the mass grave’s location.

The Earlier Fortification: Fort Hovey/Curtis

Before Fort Davidson, Fort Hovey was later renamed Fort Curtis in honor of Major General Samuel R. Curtis. Constructed in 1861, Fort Curtis was equipped with various artillery. However, its location was deemed less than ideal to safeguard local iron reserves and a nearby railroad.

As a result, Fort Davidson was built closer to Pilot Knob in 1863, boasting a hexagonal design with earthen walls. The specifics of the fort’s wall dimensions vary according to different historians.

The fort also featured rifle pits and an underground magazine, shielded by layers of dirt and wood. Despite its strategic placement, the surrounding mountains presented defensive challenges.

Around the fort, a moat provided an additional defensive layer, with its depth being debated among historians. The fort was named in honor of Brigadier General John Wynn Davidson.

The Confrontation: Battle of Fort Davidson

In September 1864, Confederate Major General Sterling Price led an army from Arkansas into Missouri, targeting St. Louis and threatening the Union’s control of Missouri. On discovering a Union force in Pilot Knob, Price decided to engage.

The Union force was led by Brigadier General Thomas Ewing Jr., who had previously made unpopular decisions that affected Missouri’s civilians. On September 27, after initial skirmishes, Confederate forces attempted to break Fort Davidson but faced significant resistance from the fort’s artillery and defenders.

Despite several assaults, the Confederate troops couldn’t breach the fort’s walls. Planning to continue the battle the following day, Price was unaware that the Union forces chose to evacuate the fort at night, setting off a massive explosion.

The aftermath of the battle witnessed hundreds of casualties on both sides, with Confederate soldiers burying the fallen in a mass grave.

Post-War Developments: Battle of Pilot Knob State Historic Site

Following the war, the fort’s area served various purposes before establishing the Battle of Pilot Knob State Historic Site. Over time, the site changed hands and saw various commemorative events.

Efforts to make it a national battlefield initially failed. The site eventually transitioned to the control of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources in 1987.

Today, the fort’s remnants are a testament to history, with a museum, visitor center, and other amenities drawing thousands of visitors annually. Research and archaeological works have unearthed significant artifacts, illuminating the historic confrontation.

10. Fort Cap-Au-Gris

Fort Cap-Au-Gris, alternately known as Fort Independence and Capo Gray, was a short-lived defensive post established during the summer of 1813 near Troy, Missouri.

Erected during the turbulence of the War of 1812, its purpose was twofold: to monitor Native American activities along the Mississippi River and to provide a haven for settlers and soldiers alike.

Upon recommendations from the occupants of Fort Howard, the Missouri Rangers, under Nathan Boone’s guidance – the notable son of Daniel Boone – selected a site roughly 18 miles east of Troy, Missouri for the fort’s construction.

In October 1814, following the loss of Fort Johnson, the U.S. Army, led by Zachary Taylor, sought refuge within the walls of Cap au Gris.

Battle of the Sink Hole

The Battle of the Sink Hole was a notable engagement close to the fort. This occurred on May 24, 1815, postdating the War of 1812’s formal conclusion.

Black Hawk between Missouri Rangers and Sac Indians commanded the clash. Interestingly, these Sac Indians, either oblivious or indifferent to the recent Treaty of Ghent signed by their British allies and the U.S., engaged in the ambush of a ranger unit.

The encounter escalated into a prolonged standoff, resulting in casualties on both sides: seven Rangers and a single Sac combatant. By 1824, the Sac and Fox tribes relinquished all territorial claims to the region.

Legacy: The Village of Cap Au Gris

After the fort’s decommissioning, a village named Cap Au Gris sprouted around its perimeter. By 1845, the village was officially restricted, comprising two stores, a school, and a modest population of approximately 60 individuals. In 1876, an attempt was made to rename and incorporate it as “The Inhabitants of the Town of Wiota.”

However, the original name stuck in widespread usage. For a while, it functioned as a crucial shipping nexus for Troy and became relatively prosperous, hosting multiple businesses. Nevertheless, the advent of railroads diverted trade routes, and by 1888, the once-thriving town had vanished.

Related: Army Forts in Missouri

Conclusion – Historic Forts in Missouri

Missouri’s military history is profound from the earthen forts that dotted the earliest settlement regions to more elaborate structures like Fort Belle Fontaine Barracks.

A notable landmark is the French fort near Sibley Street, which boasts a historic powder magazine, a testament to the state’s early European connections.

As Union troops once marched through these grounds, the fortifications in St. Louis, and many other sites scattered from Jefferson City to Cape Girardeau.

Also, from the banks of Femme Osage Creek to the far reaches of Missouri Benton County, each location tells a captivating chapter of the grand narrative of Missouri and, by extension, the United States.

If you have visited any of these forts, we would love to hear about your experience in the comments section below.

Cory is a website owner and content creator who enjoys fishing, history, coin collecting, and sports, among other hobbies. He is a husband and father of four.

Romans 15:4 For whatever was written in former days was written for our instruction, that through endurance and through the encouragement of the Scriptures we might have hope.

Thank you so much for your work in preserving history. It has been some time since I have been to Fort Osage but your information is so very exciting that I may visit with my daughter and share a beautiful memory of a forgotten treasure. Would you happen to know if they do reinactments there? If not, what is a good place or resource to where we can witness living history?

Hi Melonie,

Fort Osage hosts an annual reenactment in the fall called Fall Muster. To learn more about the fort and it’s history you can visit their website: https://fortosagenhs.com/

I’m glad you enjoyed the article. Fort Osage would be a good learning experience for kids and adults of all ages. Another interesting place to take your daughter would be the Missouri Town Living History Museum in Lee’s Summit Missouri

Thanks for reading and thank you for your comment and question!